Critical Realism and Sea Kayaking

Critical Realism: Between Reality and Perception

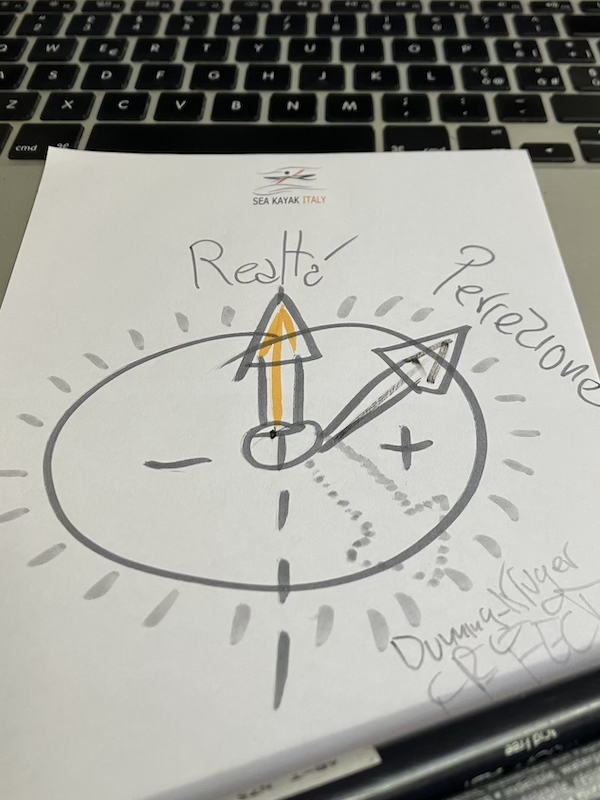

This reflection came to me while thinking about the gap between reality and perception — as if there were a small angle between the two, just like magnetic declination, the difference between true north and magnetic north.

Digging deeper, I came across the concept of critical realism.

Introduced by philosophers like Roy Bhaskar and sociologists such as Margaret Archer, critical realism emerged as a middle ground between two opposing views:

Naive realism → believes we see the world exactly as it is, without filters.

Radical constructivism → claims that what we call “reality” is merely a mental or cultural construction.

Critical realism, instead, states

“Reality exists independently of us,

but our knowledge of it is always mediated, interpreted, and improvable.”

At sea, this means recognizing that objective conditions — wind, currents, waves — have their own truth,

but what we experience of them depends on how well we can read them and how our body and mind respond.

There’s no contradiction between reality and perception: there’s a continuous dialogue.

Growth — both technical and mental — happens exactly there, where subjective experience meets objective data.

The Dunning–Kruger Effect: The Illusion of Perception

Here enters a subtle and very common psychological phenomenon: the Dunning–Kruger effect.

Discovered in 1999 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger at Cornell University, it describes a paradox:

-

Those with little skill tend to overestimate themselves.

-

Those with high skill tend to underestimate themselves.

We see it often in kayaking.

A beginner who just finished an introductory course feels “ready for anything.”

A veteran, after years of experience and awareness of the risks, still feels “in progress.”

The sea becomes a perfect mirror of our cognitive distortions:

it reflects not only our technique but also our self-perception.

The beginner’s illusion is to confuse luck or favorable conditions with real competence.

The expert’s mistake is to see the complexity too clearly — and therefore to doubt themselves.

Critical Realism as a Compass

Critical realism offers a compass for navigating these distortions.

It invites us to keep two levels of awareness constantly in dialogue:

Objective reality

The wind has a force, the sea a period, the paddle a leverage.

These facts don’t change depending on how we feel.

Subjective perception

What we believe we can handle is influenced by emotions, ego, fears, and desires.

The key is not to confuse the two levels — but to let them talk to each other.

Every time an instructor or guide helps a student compare what they feel with what’s actually happening,

they’re practicing critical realism in action.

That’s the moment when experience turns into knowledge —

when technical growth transforms into cognitive and emotional maturity.

Sea, Mind, and Humility

The sea is a strict but fair teacher.

It doesn’t punish mistakes — it exposes them.

And in doing so, it shows how often our perceptions are partial, distorted, or overly confident.

The realistic kayaker doesn’t just ask, “How do I feel?”

but also, “How reliable is my perception?”

They don’t let themselves be paralyzed by doubt — nor seduced by certainty.

They cultivate a form of cognitive humility:

the awareness that we can be wrong even when we’re sure we’re right.

In Summary

Critical realism is the inner course that connects what the sea truly is with what we believe ourselves to be.

Those who can navigate between these two worlds — with clarity, humility, and curiosity —

find balance not only in kayaking, but in life itself.